The labour force participation rate is the ratio of the employed and unemployed individuals in an economy to the working-age population. This ratio provides valuable information on critical issues such as the general health of the labour market, the potential production capacity of the economy, social demographic and social trends and the effectiveness of economic policies. Women’s participation in the labour force stands out as a vital element in sustainable development and increasing the level of welfare in modern economies. Especially in developing countries such as Türkiye, women’s labour force participation rate serves as a driving force for economic growth and plays a key role in ensuring gender equality.

It is possible to evaluate the contribution and effects of women’s participation in the labour force to national economies from various perspectives. Firstly, women’s participation in the labour force contributes directly to economic growth by increasing the production of goods and services in an economy. This participation not only increases the total labour supply but also makes the economy more dynamic and competitive by expanding production capacity. Increased participation of women in economic activities can also be one of the cornerstones of sustainable growth in the long run by encouraging innovation and productivity.

In addition, an increase in women’s labour force participation rate can lead to significant improvements in income distribution. Women’s participation in the labour market contributes to a more balanced distribution of economic welfare by increasing household incomes. This has the potential to reduce income inequalities in general and paves the way for a more equitable and inclusive development in the economic structure of society. In terms of intra-household gender dynamics, women’s participation in business life enables them to be more involved in decision-making processes and contributes to the redefinition of gender roles. Women’s economic independence strengthens women’s social status by challenging gender norms, and this can reshape the balance of power within the family.

In this study, the current situation of women’s labour force participation in Türkiye is analysed with quantitative data by taking into account education level, marital status, age and other demographic and economic variables. With this analysis, it is aimed to identify the obstacles that limit women’s participation in the labour market and to present policy recommendations for the elimination of these obstacles.

Women’s Participation in the Labour Force in Türkiye with Statistics

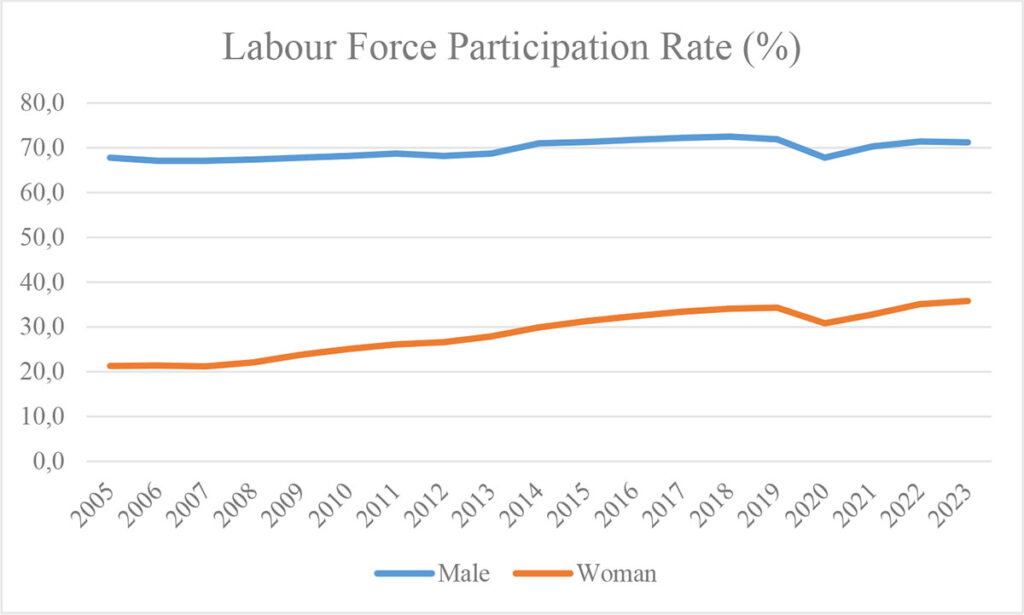

In 2023, the labour force participation rate of women in Türkiye is recorded as 35.8% and 71.2% for men (TurkStat, 2023). In the same period, this rate for OECD countries is 53 per cent for women on average, while it is 52 per cent for European Union countries (World Bank, 2023). These data underline the significant gender-based differences in labour force participation rates in Türkiye and indicate that gender inequality is still a major problem in the labour market (Figure 1). It is possible to say that women’s labour force participation rate in Türkiye is well below the averages of OECD and European Union countries.

Figure 1: Labour Force Participation Rate in Türkiye by Years

When the course of women’s labour force participation rate in Türkiye is evaluated over time, it is possible to say that it follows the distinctive “U-shaped” pattern emphasized in the existing literature. Accordingly, while the participation rate decreases for a period, it shows a continuous increase after a point that can be expressed as a “turning point period” (Goldin, 1995). According to data from the Turkish Statistical Institute, the labour force participation rate of women, which hovered around 30-35% in the 1990s, showed a continuous decline and was recorded as 24% in 2005. The rate, which hovered around 24% in the 2005-2008 period, rose to 26% in 2009 and has shown a continuous increase since that year -except for 2020, which had a pandemic effect- until today. This U-shape in the participation rate, which is also valid for Türkiye, is a reflection of the changes in the way women contribute to economic activities in the development process. The decline in the participation rate is associated with the declining role of the agricultural sector, where women constitute a significant share of the labour force, in national production and employment, and the insufficient employment opportunities in non-agricultural sectors for women with relatively low levels of education. On the other hand, the increase in the participation rate reflects the gradual return of women to the labour market in non-agricultural sectors with the rise in the level of education and the decline in fertility rates (Tunalı et al., 2021).

Education

Gender equality in education means that women and men have equal opportunities, can freely realise themselves in every field and contribute equally to the development of society. Throughout history, complete equality in participation in education has not been achieved. Especially the rate of women’s utilisation of educational opportunities is lower. For example, while education at Oxford University started in the 11th century, it was only in the 19th century that women were admitted to the university and it was only in 1920 that they were able to graduate. Today, although women’s participation in education has increased, their literacy rates are still lower than those of men. While 90 per cent of men worldwide are literate, this rate is 83 per cent for women (World Bank, 2023). This inequality is more pronounced especially in developing countries. Participation and attendance rates in education also reveal the extent of gender inequality. Boys generally drop out of education to join the labour force, while girls drop out due to marriage or family responsibilities. According to MoNE 2019 data, 0.4 per cent of boys and 4.7 per cent of girls in Türkiye drop out of school after completing the 5th grade. Gender stereotypes are also determinant in the orientation to vocational education in secondary education. While males are directed more towards vocational courses, females are encouraged more towards cultural and housework-related fields. Gender stereotypes also affect occupational preferences in education. For example, the proportion of men graduating from engineering faculties is much higher than that of women. On the other hand, women predominate in the fields of education and health. This situation clearly shows the reflection of gender roles in the field of education.

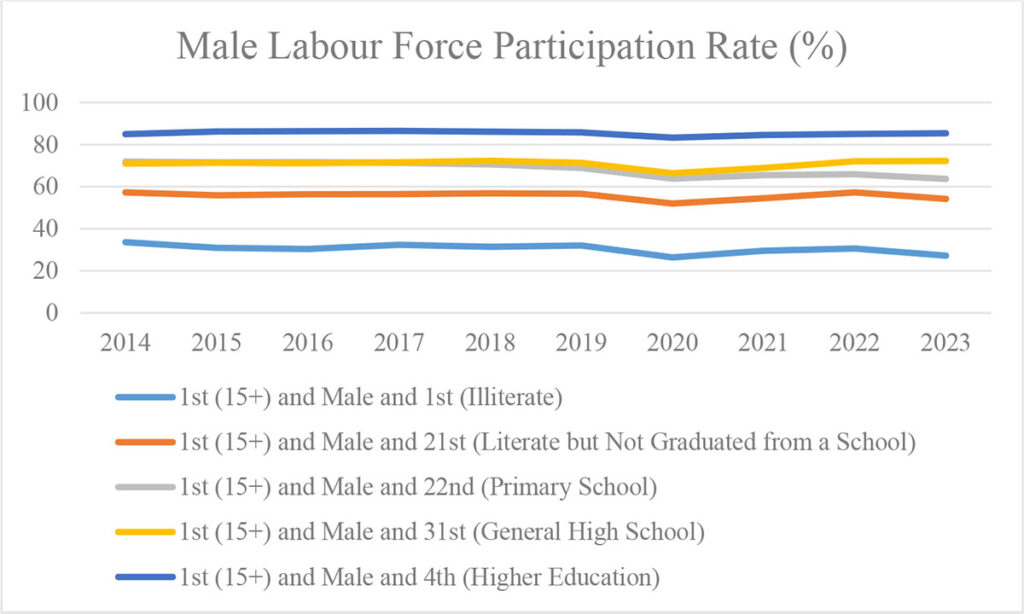

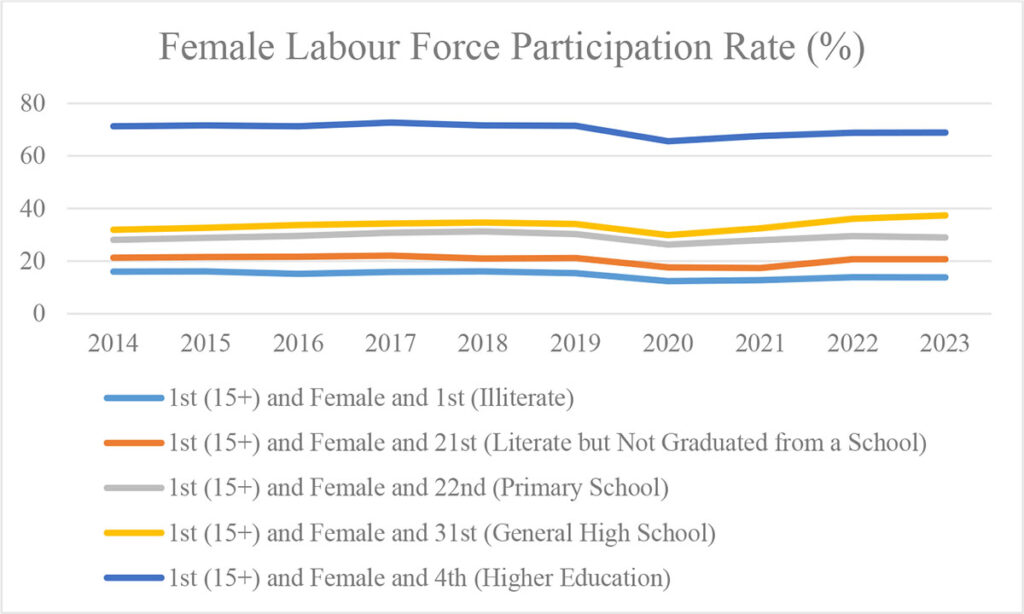

In Türkiye, women’s labour force participation rates differ significantly by education level. As seen in Figures 2 and 3, labour force participation rates increase for both men and women as the level of education increases, and this relationship becomes more pronounced especially for women. The level of education has a great impact on labour force participation. Individuals with higher levels of education are more advantageous in terms of the probability of labour force participation. Women generally underperform men in terms of labour force participation rate at lower levels of education. For example, the labour force participation rate of men who can read and write but do not have primary school education or higher is about three times higher than that of women with the same level of education. This situation reveals that the effect of education level on labour force participation differs significantly by gender.

Figure 2: Labour Force Participation Rate by Education Level in Türkiye (Male)

Figure 3: Labour Force Participation Rate by Education Level in Türkiye (Female)

When the sub-divisions of the latest data are analysed, for example, according to the Household Labour Force Survey (HIA) 2022 data, while the labour force participation rate of illiterate women is 13.9%, the labour force participation rate of women with tertiary education reaches 68.8%. Higher education level offers several advantages that facilitate women’s entry into the labour market. Firstly, education increases the level of knowledge and skills of individuals and ensures the formation of qualified labour supply in the labour market. On the other hand, educated individuals are better equipped to access better job opportunities, which in turn increases labour force participation rates. For example, while the labour force participation rate for women with high school graduates is 36.1%, this rate increases to 43% for women with vocational or technical high school graduates (HIA, 2022).

Education also plays an important role in transforming gender roles. In Türkiye, traditional gender roles are one of the important factors preventing women from participating in the labour force. However, higher levels of education help women to question these roles and to pursue broader career opportunities.

Gender

Gender equality in working life is an issue that needs to be addressed from a very broad and multidimensional perspective. Although labour force participation rates are generally highlighted in the literature, gender equality is not limited to these rates, but also covers many topics such as the sectors, industries, the structure of business lines, the wages women work in, the wages they receive, the rights they have, and the quality of work.

However, before addressing gender inequalities in working life, it is necessary to mention the changes in the concept of “work” over time. Since the early 20th century, with the development of industrial sociology, research on women’s labour has focused on defining women as individuals who work for wages in the industrial, service and agricultural sectors. There are several main reasons behind this approach and the narrow concept of “work”. First of all, these sociological studies have been conducted in industrialised countries where women participate most intensively in paid labour outside the home. In addition, it is possible to say that there is a strong “family ideology” that women should undertake domestic responsibilities such as housework, childcare and household organisation. Such domestic work is not perceived as work, but rather as tasks performed out of a sense of responsibility and altruism.

From a historical perspective, the concept of “working life” in the pre-Industrial Revolution period has a quite different meaning from what we understand today. Before the Industrial Revolution, since the production process was not mechanised and mass production was not carried out, the labour of the individual was not subject to a gender-based segregation and was not categorised as in or out of the market. However, with the Industrial Revolution, it is possible to say that the production structure and market dynamics changed and the labour of the individual was separated for the home and the market. In this process, domestic labour, which can be described as “invisible labour”, was assigned to women and market labour was assigned to men. When this emotional labour, which women undertake for free, is defined as a product of emotions such as love, motherhood and compassion, it becomes clear how important it is for the continuity of the capitalist system. After the Industrial Revolution, the unpaid labour of women against men who work outside the home and earn money has played a critical role in determining the social roles of both sexes. The concept of work has been largely identified with activities performed outside the home (Özkaplan, 2009).

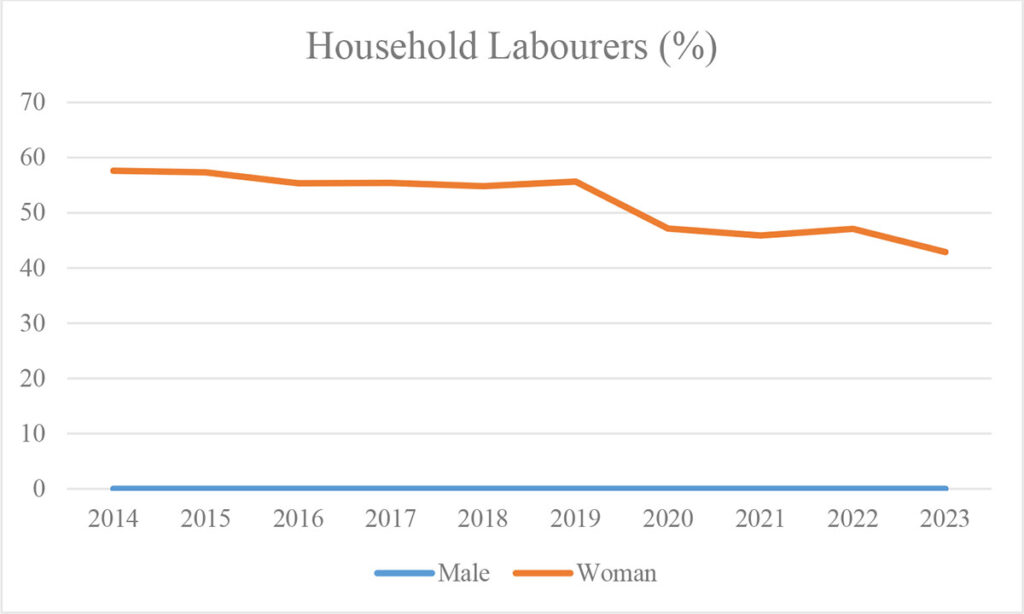

Prior to the Second World War, women’s labour worldwide was largely associated with home, childcare and elderly care and was excluded from the market. During the period from the Industrial Revolution to the Second World War, the idea that women’s main task was housework and childcare was dominant. Decisions about the labour market and working life were made collectively by the household, not by individual women. After the Second World War, women were engaged as a “reserve labour force” and refused to leave the labour market over time. Although the distinction between unpaid domestic labour and paid labour was made in the post-WWII period, it is not possible to make a clear distinction in practice. The concepts of “double shift” and “triple shift”, which are frequently used for women today, clearly reveal this situation. “Double shift” and “triple shift” are terms used to describe the additional burdens women face in the labour market. Double shifts refer to a woman working professionally during working hours and then returning home to take care of household chores. Women undertake tasks such as house cleaning, cooking and laundry after work or in their “free time”. Triple shift, on the other hand, is used for women who work and have children. This concept implies that women have to take on additional responsibilities after work, such as childcare in addition to housework. In this case, in addition to their professional work, women are also involved in household chores as well as the care and education of their children. Since this situation is mostly not experienced by men, it is considered as an indicator of gender inequality. In this context, as seen in Figure 4, although there is a decreasing trend in the rate of women not participating in the labour force due to being busy with housework, it is understood that men do not have a similar situation of not entering the labour market due to housework.

Figure 4: Proportion of Women/Men Not Participating in the Labour Force Due to Housework

After briefly examining the development of the concept of work, it is necessary to mention the position of women in paid employment in the labour market today. In every industry, from agriculture to industry, from the service sector to self-employed or employers, women generally work at smaller scales, with lower productivity and have difficulty in promotion. It is also observed that women are mostly employed in the informal sector or in part-time jobs and therefore lack social security (Öztürk and Başar, 2018). Especially in the agricultural sector, female labour force is concentrated and jobs in this field are generally low-paid and precarious. In addition, due to the dissolution in the agricultural sector, especially in the last 30 years, migration from the village to the city has caused women who are included in the labour force in the countryside to not be included in the labour force when they come to the city and to become only caregivers. The transfer of this burden from mothers to daughters is also frequently observed. In households and neighbourhoods/ districts where today’s poor adults live, issues such as how much can be spent on children’s education and health, the quality of their physical, emotional and cognitive development, including their nutritional status, the extent to which household- and place-specific constraints are overcome or binding, whether parents have wealth to transfer to their children, etc. are central determinants of intergenerational immobility. Within existing formal and informal social policy frameworks, income immobility, wealth immobility, education immobility and health immobility, which already interact with each other, determine how urban poverty evolves from the present to the future. For example, it should not be forgotten that a household that cannot finish school due to health problems, that is deprived of a regular income because it cannot finish school, that cannot accumulate wealth because it is deprived of a regular income, whether or not it is subjected to social exclusion for all these reasons, may pass on its poverty and deprivation, together with its intangible elements, to its children who do not receive adequate nutrition and fail in school. Similarly, the systematic inability of girls to access/be deprived of education and the fact that they are the main undertakers of care labour are also transferred from mothers to daughters within the household and appear as a factor that creates intergenerational immobility, especially for women. In this respect, it is necessary to identify where the inequalities and immobilisations that limit capabilities lie and to develop active social policy reforms that will free people from material and non-material deprivations in order to break the cycles of poverty (Dedeoğlu, 2000).

Demographic Factors

Women’s labour force participation in Türkiye is significantly shaped by demographic factors. These factors include various factors such as age, marital status and number of children. Although women’s labour force participation in Türkiye does not follow a very clear pattern with respect to age, it is characterised by a globally widespread “M” shaped trend. This trend starts with women’s active participation in the labour force, followed by women leaving the labour force, often at their most productive age, due to marriage and childcare. When the children grow up, women return to the labour force, constituting the third stage of the “M” pattern. Finally, these women who return to their careers withdraw completely from the labour force upon retirement (Biçerli & Özer, 2003). This cycle causes women to be disadvantaged in career development and salary increases.

One of the most important factors affecting women’s labour force participation is their marital status. Deep-rooted and entrenched norms on gender roles make it almost mandatory for women to strike a balance between work life, domestic responsibilities and childcare after marriage. These norms may negatively affect women’s labour force participation after marriage and may result in lower labour force participation rates for married women than for unmarried women. On the other hand, marriage status may affect women’s labour force participation not only when they have children but also even when they do not have children (Dayıoğlu and Kırdar 2010, Kılıç and Öztürk 2014). This can be explained by the fact that social norms expect women to undertake domestic roles. Especially the status of having children and the number and age of children significantly affect women’s labour force participation decisions.

According to the 2016 Family Structure Survey, the day care of children aged 0-5 is undertaken by mothers in 86 per cent of households in Türkiye. This is one of the most important factors limiting women’s participation in the labour force. After mothers, grandmothers are the next childcare providers with 7.4 per cent. While the rate of care provided in a nursery or kindergarten is only 2.8%, the rate of care provided by a caregiver/babysitter is 1.5%. These data clearly show that one of the main reasons behind the low labour force participation rate of women in Türkiye is the young children who need to be taken care of at home. In addition, this situation constitutes a major obstacle to women’s participation in the labour force and poses a significant challenge in achieving gender equality. The fact that women have to assume the responsibility of childcare limits their potential in the labour force and slows down the process of gaining economic independence.

Evaluation and Policy Recommendations

An analysis of the 2023 results of the Global Gender Gap Report, which has been published regularly by the World Economic Forum (WEF) since 2006, shows that Türkiye ranks 129th among 146 countries. This low ranking reveals serious problems in gender equality in Türkiye. There are many factors limiting women’s labour force participation in Türkiye. Legal regulations, sociocultural structure of the society, glass ceiling effect, regional differences and rural-urban segregation are among the main factors that make it difficult for women to integrate into business life. In this framework, it is necessary to develop comprehensive and multifaceted policy recommendations to increase women’s labour force participation in Türkiye. One of the first and most important steps to be taken in this context is the implementation of comprehensive training and skills development programmes to increase women’s competitiveness in the labour market. Vocational training and certification programmes need to be expanded to support women’s participation in the labour force. Providing training opportunities to increase the representation of women in sectors such as technology, engineering and finance is of great importance for women to be able to participate effectively in these fields.

Another critical step is to develop policies to eliminate the inequalities that women face in terms of care labour. To this end, strategies that will create a radical transformation in gender perception should be developed in the long term, while flexible working models and widespread nursery and childcare services should be provided in the short term to ease the burden of care on women. In order to encourage women’s participation in the labour force, it is also crucial to organise media campaigns to raise public awareness on gender equality. These campaigns should include strong and effective messages supporting women’s active role in business life. In addition, it is necessary to introduce more strict legal regulations against gender discrimination in the workplace and to establish mechanisms to effectively monitor such cases. The deterrence of legal regulations plays a critical role in reducing discrimination in the workplace.

Finally, beyond the existing regulations, it is important to provide financial support to employers to encourage women’s employment. These supports will encourage practices to increase women’s participation in the labour force and make employers more sensitive to this issue. Moreover, the implementation of regulations such as gender quotas to increase the representation of women especially in management positions, will have lasting and positive effects on achieving gender equality in the business world. Such policies will ensure that gender equality not only remains a goal but also leads to concrete results.

Sources

Dayıoğlu, M. & Kırdar, M.G. (2010). Determinants of and trends in labor force participation of women in Türkiye, World Bank Group. United States of America. Retrieved from https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/khhprq

Dedeoğlu, S. (2000). Family and women’s labour in Türkiye in terms of gender roles. Society and Science, 86(3), 139-170.

Goldin, C. (1995) ”The U-Shaped Female Labour Force Function in Economic Development and Economic History”. In: Schultz TP (Ed.) Investment in Women’s Human Capital and Economic Development. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 61-90.

Kılıç, D., & Öztürk, S. (2014). Barriers and solutions to women’s labour force participation in Türkiye: An empirical application. Journal of Amme Administration, 47(1), 107-130.

Özer, M., & Biçerli, K. (2003). Panel data analysis of female labour force in Türkiye. Anadolu University Journal of Social Sciences, 3(1), 55-85.

Özkaplan, N. (2009). Emotional labour and women’s work/men’s work. Labour and Society, 2(21), 15-24.

Öztürk, S., & Başar, D. (2018). Women’s labour market preferences in Türkiye: An analysis specific to the informal sector. Journal of Social Security, 8(2), 41-58.

Tunalı, İ., Kırdar, M. G., & Dayıoğlu, M. (2021). Down and up the “U”-A synthetic cohort (panel) analysis of female labour force participation in Türkiye, 1988-2013. World Development, 146, 105609.